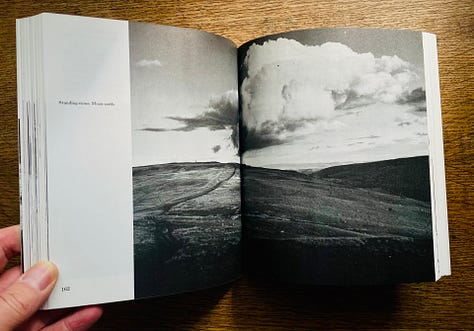

Fay Godwin (1931-2005) was one of the greatest photographers of the British landscape. She had no formal training in photography and shunned academic theory, saying she preferred to do the work instead. Also wary of the picturesque, she took a documentary, descriptive and objective approach. She became president of the Ramblers Association and a passionate advocate for more and better access to our land.

Godwin depicted Britain as an archetypal terrain of megaliths and ancient roads, moors, woodlands and rocks as desolate and austere as an abandoned country. She juxtaposed these timeless landscapes with manmade landmarks and signs of worked land - the wild and the cultivated, the wilderness and habitation. She showed the evidence of human activity, but rarely people themselves in place.

Her photographs were collected in large format books like Land, Our Forbidden Land and Landmarks. She collaborated with writers - including Ted Hughes and John Fowles - but her photographs weren’t included only to illustrate someone else’s words. She was an equal partner in the creation of these books.

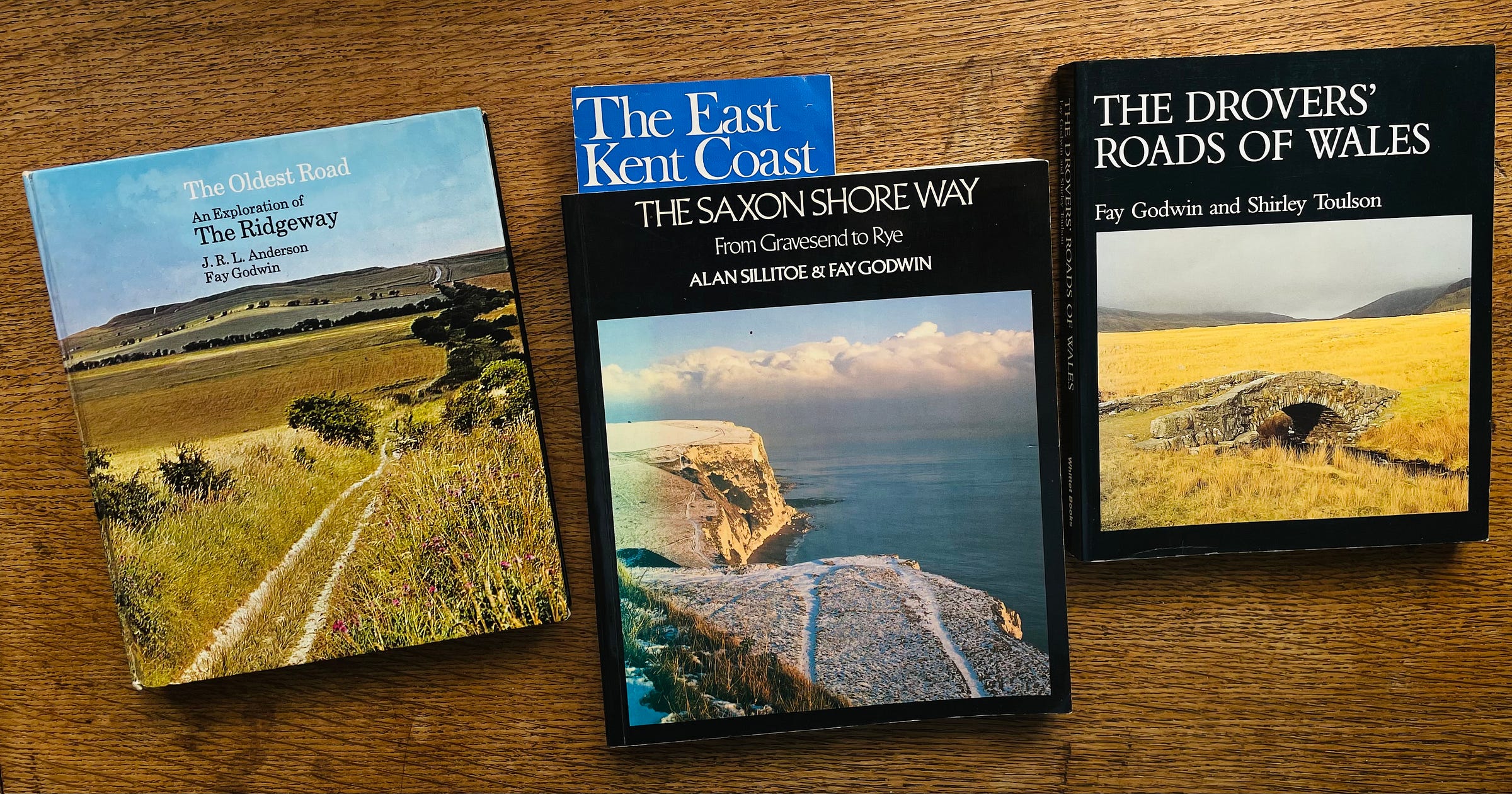

The three I’m looking at more closely here are less well known, perhaps because they were published as walking guides in the Seventies and Eighties and are assumed to be out of date. I bought them because I wanted to see more of Godwin’s pictures in their original context and I found the texts well worth my time as well. Each author takes a different approach to writing about walking, landscapes and history. They’re all full of interesting details and still useful, to some extent as guides, certainly for background reading.

All of Fay Godwin’s books are now out of print, but most of them can be found affordably secondhand.

The Oldest Road: An Exploration of The Ridgeway

with JRL Anderson

This was Fay Godwin’s first book, from 1975. JRL Anderson was a Guardian journalist and wrote thrillers and books of real life adventures, including an account of sailing from England to North America via Iceland and Greenland in 1966 to replicate Leif Erikson’s voyage to discover Vinland in 1001 AD.

We have mostly lost our sense of religio loci - the spirit of a place - of standing on hallowed ground, but Anderson does his best to look at the Ridgeway in that way. His introduction promises ‘a sort of four-dimensional guide book, with signposts for travellers in time as well as in terrestrial space, an interpretation of the peoples and cultures which have left their mark on the area, notably the Great Stone Culture and the men and women of the Arthurian and Saxon kingdoms.’

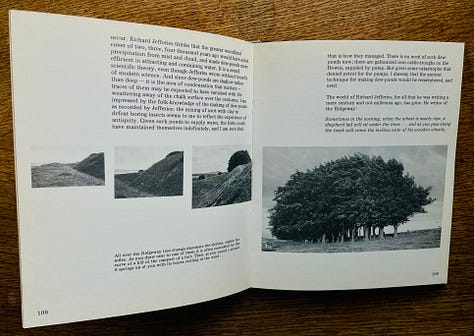

Roads are man’s most enduring works. A natural path becomes a work of man as each traveller marks the way for the next. Our feet follow footsteps and so a road is trodden into history. Traversing well-trodden paths can open up a portal to the past to commune with all those who have walked that way before. The England of the ancient past and the present co-mingle.

The Ridgeway is the oldest road in Europe, walked since the Old Stone Age before Britain was an island, before the last ice age, by travellers, soldiers and herdsmen. It’s neither a farm track nor a king’s highway and leads nowhere in particular. Along the way you pass the Iron Age hill forts at Barbury, Liddington and Uffington, many long barrows and ancient burial sites of our ancestors. The Ridgeway proper is fifty miles or so long and feels unbelievably remote, with a deep sense of loneliness and isolation. Like being at sea, you can see the true horizon all around.

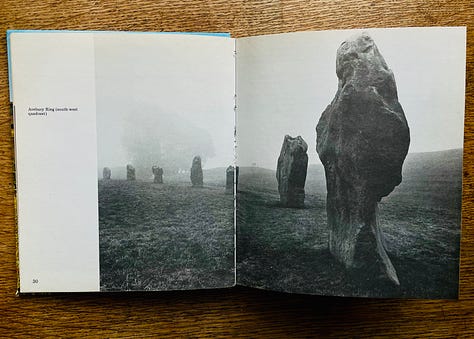

It starts near Avebury in Wiltshire, which was once the metropolis of prehistoric England. A network of routes led to Avebury a thousand years before Rome was ever built. Godwin’s photos of the stone circle here capture the character of individual stones.

Along the way is Barbury Castle which the British defended against the Saxons in 556. Anderson summons the spirit of King Arthur keeping the Saxons at bay for a generation, ‘long enough for a whole world of legends to be created round it, long enough to remain in folk memory as a golden age to which later people could look back with longing and with wonder.’

Later you come to Wayland’s Smithy where, the tale goes, you can leave your horse by the tomb with a coin on the lintel stone and return to find it shod by Wayland, the smith of the old Saxon gods. In reality, though, this is an early megalithic long barrow that stood here two thousand years before Saxon gods were heard of here.

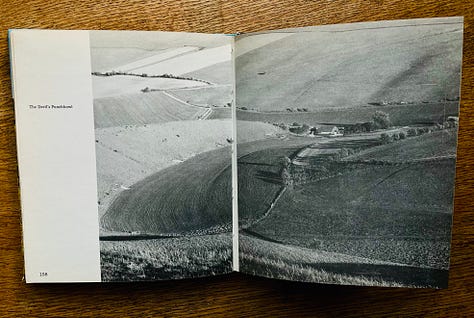

Near the village of Bishopstone you find prehistoric strip lynchets, which are terraces cut into the hillside for growing crops. You will also come across the Uffington white horse, the Devil’s Punchbowl, Grim’s Ditch and Scutchamer Knob.

At the end the Ridgeway descends to the Thames, where it was held by Alfred as a boundary against the invading Danes.

There are many great photos in this book, but most of them are small and the print is slightly faint. It’s still worth getting for Fay Godwin fans, but Anderson’s writing was a revelation to me. I expect some of his bold historical interpretations and yarns have been outdated by advances in archaeological knowledge, but his speculations are still a great read.

The book also includes many well-drawn maps. You could still use it as a guidebook because the Ridgeway is an easy route to follow and nothing much has changed along the way since it was published in 1975.

Here’s a reading list of some of the books JRL Anderson refers to:

Archaeology of Wessex by Peter Fowler

The Age of Arthur by John Morris

Wild Life in a Southern Country by Richard Jefferies

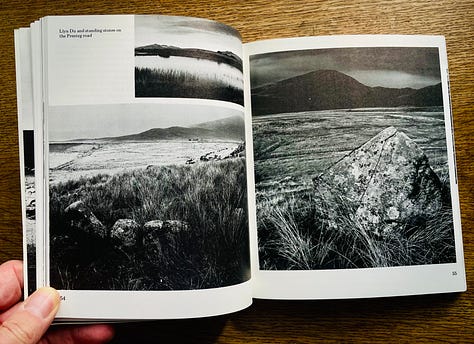

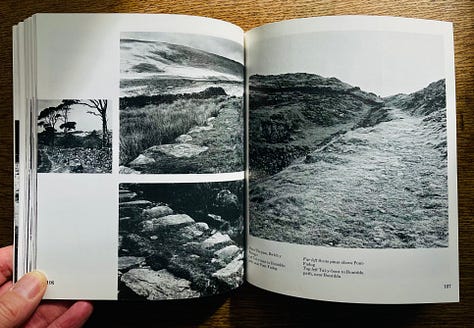

The Drovers’ Roads of Wales

with Shirley Toulson

This, from 1977, is more of a walking guide because these ways are often hard to find or follow. They are centuries-old tracks across north and west Wales that drovers used to take thousands of beasts a year - cattle, sheep and even geese - to markets in London and Kent. In these remote areas for centuries until the early Twentieth Century, pastoral farmers lived semi-nomadic lives following their grazing herds. In the summer months men satisfied their wanderlust by taking cattle across the mountains. Throughout the Middle Ages the roast beef of Merry England came this way from Wales.

Cattle were shod, the feet of geese were protected with a mixture of tar and sand and they even walked on spikes like short stilts. Pigs wore boots of woollen socks with leather soles.

The voices of the drovers were ‘neither shouting, calling, crying, singing, halloing or anything else, but a noise of itself, apparently made to carry and capable of arresting the countryside.’ These were probably among the earliest noises that man made. Words and sounds used in relation to domestic animals have undergone the least change across the centuries. These were the working noises of primitive man.

It was a hard life for the drovers - brigands and robbers saw the bags of money they carried as an obvious target - but they were well paid and well informed. In many places they were the only source of information from the outside world.

After selling his herd at market a drover would often sell his pony too and send his dog to make its own way home with the pony’s saddle on its back. Drovers would arrange for the keepers of inns where they’d stayed on the way out to feed their dogs when they returned alone. The women at home knew their men were due back in a few days when their dogs reappeared.

Scattered farmsteads instead of villages like in England. Pre-Celtic burial sites - massive stone chambers, cromlechs and long barrows in the mountains of west Wales. Iron Age hill forts in the mountains of the north

Shirley Toulson, who was also a poet and wrote other books about walks, ancient tracks and traditions of Britain, tells of the strange bleakness of these parts of Wales, of churches with circular churchyards built on sites of Celtic sacred places, of weird tales of ghostly legions marching in the hills and of the wave of evil atmosphere that runs into the marshy highlands from the Dolbenmaen hills.

The Saxon Shore Way

with Alan Sillitoe

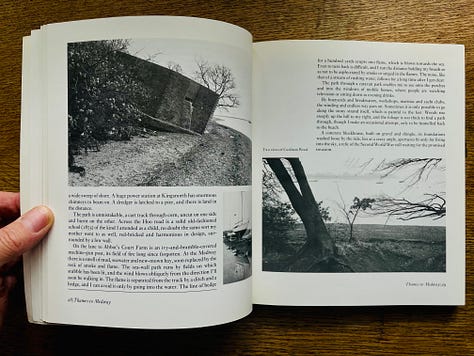

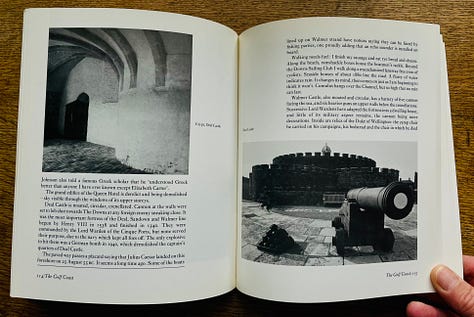

The Saxon Shore Way is an ancient coastal path running 140 miles from Gravesend to Rye in Kent, the south-east corner of England. The route originally connected a series of forts built by the Romans to keep the Saxons at bay. A coastal, rural, industrial, military and historial land- and seascape.

Alan Sillitoe was the author of novels including Saturday Night and Sunday Morning and The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, both of which were filmed in the 1960s.

He’s a friendly and informative guide, telling historical anecdotes and about the pubs and cafes he’s visited and what he’s been eating along the way. His account reflects the footsoreness, frustration and muddiness of a real walk, including encounters with bulls, getting a bit lost, a pub shutting just before he gets there. The book is described as reminiscent of the work of Edward Thomas, the poet and travel writer who died in the First World War.

This is an area of sailors, rebels and smugglers - ‘the cattle meadows of Ham Marshes and old ships at the wharf, with traditional barge masts and red rusty sails furled, create an ageless scene.’

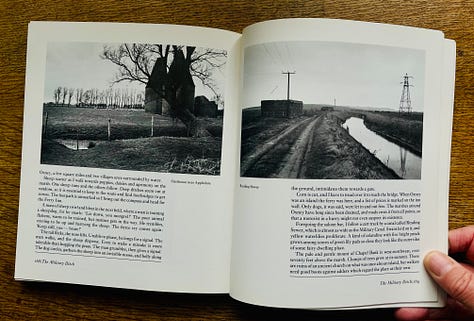

He writes of creeks of workshops and boatyards, lagoons and abandoned machinery, caravan parks and breakers’ yards, orchards, cattle, sheep and scraggy ponies. ‘Small boats lie in the mud. An enormous power station stands on the flat northern shore which is all pylons, aerial, chimneys and cranes, and a few low trees.’

There are many towns and villages all along the route and there are more urban scenes than Godwin usually shows, but as Sillitoe says when he gets away from the towns: ‘it is good to be in countryside with real horizons all around’.

I’ve not seen much of Kent myself, but I wouldn’t be surprised if much of the industrial activity Sillitoe described in 1983 has ended, so this walk, unlike the previous two, is probably quite different now.

A few links to find out more about Fay Godwin:

her official website

A wide-ranging gallery of her photography in The Guardian.

Her obituary by Ian Jeffrey

A Woman’s Hour feature from 2003

A South Bank Show from 1986: